Rickey Ayala: Basketball Pioneer and Business Success

2/12/2007 12:00:00 AM | General

Feb. 12, 2007

February is Black History Month, and nowhere in major-college athletics is that history richer than at Michigan State University. From Gideon Smith, the first African-American football player at Michigan Agricultural College in 1913, to Steve Smith, an All-American basketball player whose contributions have a major impact today, it would take many months to tell the full story. In a series of profiles, longtime Michigan State beat writer and columnist Jack Ebling will highlight some of the greatest of the great. The second of those stories is basketball pioneer and business success Rickey Ayala.

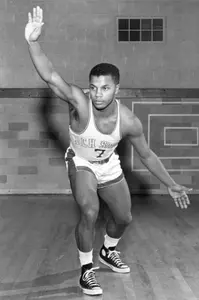

RICKEY AYALA

He wouldn't take no for an answer. But he was more than the answer to a trivia question: "Who was the Spartans' first African-American basketball player?"

First and foremost, Reginald "Rickey" Ayala was a natural leader. Born in Puerto Rico and raised in New York, he defied the odds again and again. At 5-foot-6, 158 pounds, his heart was as big as any 7-footer's.

As a star at Brooklyn Technical High School, Ayala decided he just had to play for Coach Pete Newell at Michigan State College. And he knew he wanted to bring his boyhood buddy, Al Ferrari, with him.

"Rickey wanted to come with me because he knew I played small guards," said the legendary Newell, whose 1949 San Francisco team with 5-9 Rene Herrerias had ruled the NIT - then the nation's top basketball event at any level - in Madison Square Garden.

"But when he showed me his transcript, I said, `You couldn't get in a reformatory with this!' He said, `If I get in, will you let me come out for basketball?' I said, `If you can get in with this, you can do all the recruiting for me!'

"Sure enough, when school started, Rickey showed up. To this day, I don't know how he got in. I didn't know anyone in admissions who could've helped him."

As always, Ayala knew what he wanted and promptly went about getting it. That persistence worked wonders with his MSC admission, with Ferrari's recruitment, with the Harlem Globetrotters and in a distinguished career in hospital administration.

"I had to come back to campus by automobile and said, `Why don't you come with me, Al, and look at the campus?'" Ayala said in 1998. "When we got there, I took him straight to Jenison. We wound up in a pickup game against Leif Carlson and Erik Furseth, a couple of real hatchet men.

"The funny thing was, his recollection of me was that I was a star. He kept feeding me the ball. Finally, I said, `I'm going to give you the ball!' He said, `Is it OK if I fight back?' After that, we tore them up." It wasn't the last time Ayala and Ferrari won a few bucks from unsuspecting rivals. And in 1952, they won the respect of the nation's No. 2 team, Kansas State - still the highest-ranked squad to lose a game in East Lansing.

"I remember the State Journal saying, `Come see Kansas State. . . . Oh, by the way, Michigan State might show up, too,'" Ayala said. "We showed up, all right! When Kansas State called time, the score was 11-1 (in an 80-63 shocker). It was Al's finest performance. No one could've guarded him that night, except Jesus."

Ferrari wasn't the only player Ayala tried to attract to the program. Duquesne great Sihugo Green was ready to transfer under Ayala's spell until Newell said no.

I said, `Rickey, you can't do that,'" Newell remembered. "He said, `I know. . . . But Coach, he could really help us."

It seemed Ayala was always into something. And Ferrari wasn't far behind.

"You never knew when Rickey was running a scam on somebody," Newell said. "He'd get the Indiana guys and play them for money. I think Rickey financed his first two years of school with those two-on-two games. He was so damn smart - a coach on the court but smarter than most of us."

Newell was no dummy, either. He devised a strategy to encourage teams to post up Ayala, a great defender and the team's third-best rebounder. Invariably, Ayala got the best of that deal. Once, he even let Minnesota score an early basket to build false confidence. By the time the Golden Gophers realized what had happened, they had three players in the wrong positions.

When Newell finally bribed and steered Ayala into a new major, hotel and restaurant management, he faced an unavoidable conflict with classes. That led to a failing grade in accounting, which wound up being his strong suit before he left campus in 1954.

"They had this really ridiculous rule that you were ineligible if you flunked one class, regardless of your grade-point," said Ayala, who couldn't play all winter quarter. "There was a misunderstanding. It was my fault. And I regret it to this day. That was the finest team I ever played on."

Ayala rebounded again and played on another outstanding team, the Globetrotters, for two seasons, sandwiching a two-year stay in the U.S. Air Force. That preceded a tremendous career in business, including 32 years as the chief executive officer of two Detroit hospitals, Kirkwood and Southwest Detroit.

In 1997, Ayala was honored with the MSU basketball program's Distinguished Alumnus Award. And to hear Ferrari and Newell tell it, Ayala also earned the designation as the school's best unpaid recruiter.

He died on Feb. 3, 2000, at Sinai-Grace Hospital in Detroit.