Alan Haller: Defensive Back-Turned-Police Officer

2/28/2008 12:00:00 AM | Football

Feb. 28, 2008

February is Black History Month, and nowhere in major-college athletics is that history richer than at Michigan State University. From Gideon Smith, the first African-American football player at Michigan Agricultural College in 1913, to Steve Smith, an All-American basketball star whose contributions have a major impact today, it would take many months to tell the full story. In a series of Spartan profiles, longtime writer and radio broadcaster Jack Ebling will present some of the greatest of the great in 2008. The sixth is defensive back-turned-police officer Alan Haller.

ALAN HALLER

Some people command respect, regardless of their uniform. Alan Haller does that to this day, two decades after his Michigan State debut.

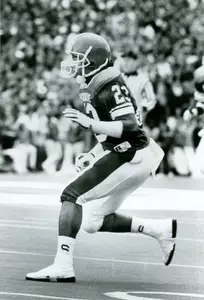

On the football field, he was a cornerback on a championship defense in 1990, bringing honor to No. 23 - a famous jersey in Spartan lore.

In the field he chose to pursue after his NFL days, Lt. Haller has been a major contributor to the MSU Department of Public Safety.

Haller's recognition of authority shouldn't have been a surprise to anyone. Born in Milwaukee, he moved to Lansing as in third-grader. His mother was a teacher in the East Lansing schools and his father a pastor.

"I never thought of myself as special," Haller said. "I remember when we played tag; I was never `it.' But I played offensive and defensive tackle in flag football. My coach was (former Spartan) Kermit Smith. Finally, we raced, and I beat everybody."

His vivid memories include four years of football and track at Lansing Sexton, where he starred for Gary Raff, Bob Meyers and the legendary Paul Pozega.

Haller's life changed forever as a freshman when Raff and Meyers took Haller to a fourth-floor hallway and asked Pozega to clock him in a 40-yard dash.

"When I said I thought I'd go out for baseball, Coach P. said, `Oh, no, you're not!'" Haller said. "I never left the fourth floor. I guess my time must've been OK. The next day, I was on the indoor track team. That was usually only for juniors and seniors."

Haller didn't love track immediately. He suffered from severe asthma and would have to sit out a series or two every time he had a long run in football. But even on three or four medications, he loved to win.

"Whoever the starting running back was at Sexton in those days was always going to be a star," Haller said with his usual modesty. "But I didn't have helicopters landing on the practice field when I was being recruited, the way James Moore did." His choice of schools came down to Indiana, Michigan, UCLA and MSU. A less mature prospect might have wound up at Westwood.

"I had a tough time with the choice," Haller said. "I'd grown up around Michigan State's camp. I always felt at home there. But when I went to UCLA, Mike Farr was my host. He lived a different lifestyle. For a while, I thought everyone there lived that way."

George Perles made sure Haller came to his senses. And with help from assistants Charlie Baggett and Nick Saban, the Spartans kept a homebody home.

"Even when I was doing well in high school, I never really saw myself as a running back," said the No. 6 player on the Lansing State Journal's "Catch 22" list of in-state recruits. "I always wanted to be a DB. I liked to cover people and be on an island."

Haller liked watching Deion Sanders and got a close-up his freshman year when "Neon Deion" went at it with MSU All-America split end Andre Rison in Tallahassee.

Sanders wore No. 2 in those days. So when Haller had to settle for jersey 23 instead of the 33 he wanted, it turned out to be a perfect combination.

"I wanted 33 because of Tony Dorsett," Haller said of the 1976 Heisman winner. "Somebody beat me to it. But when I got 23, a message said, `Wear this with pride.'"

Quarterback Steve Juday had worn it in a Rose Bowl. Flanker Kirk Gibson had worn it as a two-sport terror. And current running back Javon Ringer has kept it in the highlights. But no one ever wore 23 with more class.

"The one thing I miss to this day is being with my teammates and working toward a common goal," Haller said. "I've tried to get that feeling in every job I've had but haven't found it again. Even when we didn't agree with each other, we were in it together. That's why we led the Big Ten in defense three times in four years."

His most memorable moments came amid errors in 1988 and 1990 at Michigan - one crushing loss and one unforgettable triumph.

"We blocked a punt and ran it back my freshman year, but I was offsides," Haller said. "Coach Perles gave me that look and motioned me over. I thought he was going to kick me off the team. Instead, he said, `Hey, kid, just watch the ball.' I never forgot it."

Haller saw teams try to run and pass with little success. And even when he gave up a touchdown or two, his coaches and teammates were there to help.

"The '90 win over Michigan still gives me chills," Haller said. "We came out of the locker room and were held up by a guy from ABC. I was right behind Coach Perles, and he moved the guy's hand. He said, `We're ready now!'" A 28-27 upset in the "No. 1 vs. no one" game was sealed when opposite corner Eddie Brown helped the Wolverines' Desmond Howard drop a two-point conversion in the closing seconds, and then intercepted a Hail Mary heave after an onside kick.

"There's a lot to take from that game - lessons for life," Haller said. "I'd been beaten by Derrick Alexander and probably would've been the goat if not for Eddie."

If MSU had won more games in 1991, Haller wouldn't have been free to star for Perles in the Blue-Gray Game and the Japan Bowl and might not have been picked in round five by his coach's former NFL team, the Pittsburgh Steelers.

"With Pittsburgh, Cleveland and Carolina, I`d say I was stressed out 95 percent of the time," Haller said. "I was cut eight different times."

Saban tried to talk Haller into becoming a coach. But a career in criminal justice beckoned. Again, timing was everything. And he was smart enough to seize that chance.

"I wasn't even going to apply on campus," Haller said. "When I stopped to pick up my transcript, I dropped off a resume and had a call by the time I got home."

For his master's in public administration, Haller got special permission from Central Michigan to write about the post-competition transition for elite athletes. Few have ever done it better, though Saturdays are spent in a blue uniform, not a green one.

"I had no idea how big a deal college football was till I was out of the academy," Haller said. "The first year, I was on the sideline and spent all my time watching the DBs. But I couldn't believe all the traffic and the parties."

He should've seen the party when the Spartans beat U-M and won a Big Ten title.