HIS WAY

6/13/2008 12:00:00 AM | General

June 13, 2008

Video Coverage from Media Roundtable

Ron Mason AD Highlights

Listen to Spartan Sports Podcasts:

Ron Mason Media Roundtable

MSU Athletics Director Mark Hollis on Ron Mason

Denver head coach George Gwozdecky on Ron Mason

CCHA Commissioner Tom Anastos on Ron Mason

By Jack Ebling, Online Columnist

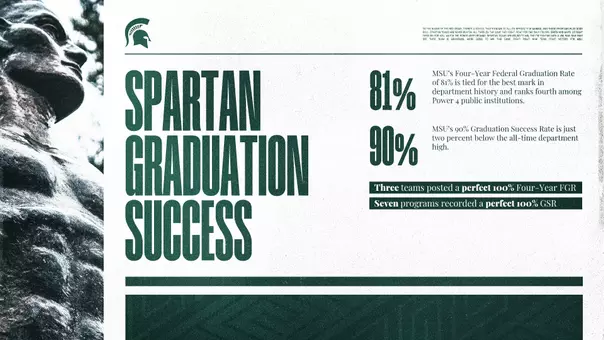

He finished his college coaching career with an NCAA-record 924 wins - 22 more than Bob Knight and 174 more than Bobby Bowden and Joe Paterno combined.

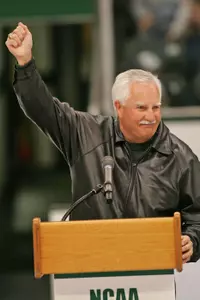

But hockey icon Ron Mason had other triumphs.

His greatest accomplishment? Not Michigan State's 1986 National Championship win over Harvard. Not the maturation of the CCHA, where teams compete for the Mason Cup. And not his stint as the Spartans' director of athletics, a last-chance career change.

Mason's No. 1 achievement was sticking to his principles, ones he learned from his parents, Agnes and Harvey, more than six decades ago.

His mom was a terrific teacher, his dad more of an administrator than an athlete after suffering a broken back. But the one thing that was never broken was their son's indomitable spirit.

An always-determined, often-stubborn leader - and cue Sinatra for his favorite song here - the pride of Blyth, Ontario, did it his way.

"I think I tried to follow the rules and do things right," Mason said before Thursday's night gala salute. "That's not as hard to do in hockey as some other sports. But people still try to cut corners and think of the short term. I knew I was in it for the long term."

That term began in 1966 and lasted nearly 42 years, 36 as a head coach and six as an AD.

In seven seasons at Lake Superior State, six at Bowling Green State and 23 at MSU, Mason's teams won 20 or more games 30 times and 30 or more on 11 occasions.

He coached in 24 NCAA Tournaments, reached eight Frozen Fours and scaled the summit 22 years ago with a team that wasn't supposed to be his best.

"A championship is a statement," Mason said. "We'd never won it all. And that was all anyone talked about. We won an NAIA title at Lake Superior. But no one ever talks about that. I firmly believe we should've won three or four times with the teams we had here."

Pressure was always a problem, Mason said. And when expectations and injuries intersected, he had to settle for one more national title than Coach of the Year contemporaries and conference kings Bo Schembechler and Gene Keady.

But with 25.67 victories per season, Mason's career wins reached Gretzky-esque levels - 121 more than second-place Jerry York, his successor at Bowling Green and the reigning NCAA champ at Boston College.

When it comes to college coaching trees, Mason's must be a giant sequoia. And the limbs from its trunk are truly majestic. Has any other leader in any sport produced four protégés with multiple NCAA crowns? That's what Mason has done with Rick Comley, Jeff Jackson, Shawn Walsh and George Gwozdecky.

"Everyone should have a mentor, and I was lucky enough to have the best hockey mind in North America to learn from," Gwozdecky, a back-to-back champ at Denver, said. "Despite everything that's happened, those five seasons with Ron at MSU were the most memorable years of my life. We were all in it together. The relationships were incredible. And I've tried to carry that on wherever I've been."

Gwozdecky, the only one with NCAA hockey titles as a player, an assistant coach and a head coach, is 451 wins from the top spot. Comley, who succeeded Mason at Lake Superior and MSU, is 185 wins away.

Ron Mason and Rick Comley pose with the 2007 NCAA Championship trophy. |

But one of Comley's victories meant as much to Mason as any of his own. Actually, it might have meant more when his ex-Lakers captain and first hire as the Spartans A.D. answered all the critics by winning the 2007 National Championship. In a raucous winners' dressing room, the "MSU Fight Song" never sounded better.

"I probably enjoyed the last one more than my own," Mason said. "It was really fun to watch that team. They overachieved. And it was nice to see that happen for Rick. People were really down on him. He had a tough adjustment. But I knew he could do it. He proved it that night. It was great."

No one used the word "great" in the scouting report when Mason took the first faceoff in the proud history of the Peterborough Petes. But he was a smart, productive player who always seemed to be in the right spot.

"I was probably better than I thought I was," Mason said. "I was in Junior A at 16 and had a chance to play with and against some of the best in the world. I played with Ralph Backstrom and J.C. Tremblay and against Bobby Hull, Stan Mikita and Frank Mahovlich. If you played in that league, you were headed to the NHL for the most part."

Instead, Mason headed to St. Lawrence to get his education and play hockey. He was a serious student and hoped to become a professor, even when he did his graduate work at Pittsburgh. Suddenly, he found himself as the head coach at Lake Superior.

"I could've gone to Harvard," Mason said. "My mom cried when I turned it down. It just wasn't me. But if I hadn't taken the job at Lake State, I never would've gotten into coaching. I was more involved with studying the training of hockey players. The Europeans were way ahead of us. And I spent hours and hours in the library, long before we had computers, getting articles translated."

Mason's philosophy of hockey hasn't changed since he was 10 years old. A peewee coach named Johnny James gave Mason his first look at a system of play. And what worked then worked just as well when he ruled the CCHA.

"When I was at Lake Superior, we were outcasts," Mason said. "We couldn't qualify for the NCAA Tournament, only the NAIA. I would've loved to take the winner of the NAIA and play the winner of the NCAA. We'd have done pretty well. One year, we played Michigan Tech at their place and Clarkson at their place and beat them both. They were the teams that made the NCAA Finals."

The situation began to improve at a pace slower than any zamboni when Mason went to Bowling Green. Despite winning a CCHA crown, the Falcons couldn't crack the NCAA's four-team field, much to their president's dismay.

"One year, we won the CCHA Championship in St. Louis before more than 10,000 people," Mason said. "No one was drawing those kinds of crowds in those days. So our president, Hollis Moore, said, `Where are we going now?' I said, `That's it. We're done.' He said, `What do you mean we're done? . . . That's the end of this!' When he complained to the NCAA, we finally got the chance to play a play-in game."

Bowling Green lost at Michigan, beat Colorado College and lost at Minnesota in NCAA play before Mason moved to East Lansing. If those struggles nearly drove him crazy, they also showed what can happen when a great teacher and communicator is driven.

"It made me a better person, a better coach and a better administrator," Mason said. "I'd been at Lake State and didn't have much to work with. I went to Bowling Green and had more to work with. And when I came to Michigan State, I said, `My god, if we can't win here, there's something wrong!'"

The Spartans had struggled for several seasons under Amo Bessone in the late 1970s. After two rebuilding years under Mason, MSU hockey was on its way. It has been as good as any program in the country over the past quarter-century.

"Ron has been the single most important leader in the establishment and development of the CCHA," said Commissioner Tom Anastos, a former Mason forward in East Lansing. "Without his vision and persistence, the league would never have flourished. He has always pulled for the underdog and been the conscience of our sport."

Mason has done so much for his conference, his name is on its championship cup. And it's appropriate he was the first coach to hoist it after MSU won another league title.

"I always wanted to help the sport," Mason said. "I've been a firm believer if you help the sport get better, you'll get better. I scheduled developing teams because I had a developing team at Lake Superior and Bowling Green. If they beat us, it was the biggest win they ever had - like they won the Stanley Cup or the NCAA Championship. I said, `You know what? I was there one day, too. And if I can't absorb a loss like that to make the sport better, I'm not a very good person.'"

"Good" doesn't do it justice when we talk about his contributions to the sport. And from Joe Kearney, who hired him in 1979, to Mark Hollis, who succeeded him this year, MSU's ADs have appreciated Mason's approach in good times and tough ones.

"Every athletic director leaves things a little bit better than when they came in," said incoming AD Mark Hollis. "I think that's the goal and it's the role of the next AD to put another log on the fire, to just keep building upon what's been done in the past. From a coaching perspective, our coaches are extremely solid. Our budget has a very solid base that we need to continue to look at and build upon as far as allocation of our resources. The spirit is good within the department, the morale is good within the department, and we're just continuing to build upon those things that Ron (Mason), Clarence (Underwood), and others before them put together.

"I think anytime a university brings an athletic director on board they bring him for a certain purpose," Hollis continued. "At the time Ron came in, there was attention that had to be given to a number of areas. One of those was the connection back with coaches and, not to say that it hasn't been done in the past, but bringing in a coach to kind of be that father figure for the coaches was a positive. He had the support of the staff around him as far as the administrative staff. Being an athletic director very much is like being a coach because there are so many different moving parts in running an athletic program and the way he handled it was very much like a coach. He relied on his captains, his players to pull those parts together and move the department through his tenure."

"Ron has been a great one for a long time," said Doug Weaver, Mason's boss for close to a decade and close friend since 1980. "He did a super job as a coach. He was always very professional. And as a director, he came in when the job was changing. He's a very versatile guy with eclectic tastes. I'm really proud of him. I owe him a lot, and the school owes him a lot."

When Weaver decided to step down in 1989, many looked at Mason and saw a coach with an AD's skill set. One of those people was George Perles, who finally pursued and won the job at a tumultuous time. If the time had been right for Mason to leave coaching, we could be talking about an 18-year administrative reign, one with greater stability.

"Even at Lake State, I thought I might want to be an AD some day," Mason said. "But when Doug said he was leaving, George came to my office. He said, `Do you want to be AD? If you do, I'll support you.' I said, `No, it's too early for me.' He said, `If you won't do it, then I've got to be the AD.' He would've let me do it. But the timing was wrong. I wanted to keep coaching and couldn't do both jobs. How would things have changed? Who knows?"

Mason had two more opportunities to move from the ice to an administrative hot seat. Finally, when President Peter McPherson was looking for a successor to Clarence Underwood, Mason realized he wouldn't have another chance. It was do it or forget it.

"I think I'm the guy who talked him into taking the job," MSU basketball contemporary Jud Heathcote said. "I tried to get him to take it the first time. I thought we needed the continuity. What he did in hockey and as AD certainly means he'll go down as one of the all-time Spartans."

No less a legend than Michigan AD Don Canham, one of the most important administrators in NCAA history, saw something special in Mason, too. That relationship started when Canham stopped at Bowling Green to meet with the staff and was peppered with questions by an inquisitive hockey coach. Three separate times, Canham insisted Mason would be a great department leader.

"Most people are more successful in one environment than another and at one university than another," Minnesota AD Joel Maturi said. "Ron had already proven he was a great coach. But I thought administration would be more challenging for him. Instead, he was the perfect choice. He brought the `State' back to Michigan State and made it OK to be proud to be a Spartan again."

Mason made an impression on everyone he met. Some feared him. Some resented him. But most appreciated his strong beliefs and consistent results for more than four decades.

"More than anyone I ever dealt with, Ron was a helping hand," Anastos said. "And it wasn't just me. I'm sure he takes pride in the impact he has had on so many people. When I played for him, I thought he invented the sport. My understanding of the game wasn't very sophisticated, and he blew me away. He was a very good recruiter, a great evaluator of talent and a very persuasive communicator. Players had great careers who wouldn't have done much elsewhere."

"I'm not sure I can put his contributions into words," Comley said. "The thing I'll remember is his passion, that fast walk and his approach to life. Everything was done with an edge to it. He meant so much to the Comleys, Walshes and Gwozdeckys of our sport. And when a lot of people said, `Don't get out of coaching. Get to 1,000 wins,' he had a bigger challenge."

The biggest challenge for a Big Ten AD is helping to build a solid football program. When football is right, everything else is just details. And when Mason hired John L. Smith, he was sure he had it right. In fact, he still believes the Spartans were a few plays in a few games from long-term success.

"As an AD, you're judged by the guys you hire," Mason said. "When Rick proved he could do it, it was great. And I know John L. could've done it. Overall, I'm proud of what we've done."

What Mason has done is change his sport. College hockey will never be the same. And his impact might be best illustrated by what happened in early 1980 when Olympic gold medalists Ken Morrow and Mark Wells came home for a political lovefest at the Capitol.

"They were the only two players on the team from Michigan, and they'd played for me at Bowling Green," Mason said with unmistakable pride. "They had this big deal in the governor's office and told me, `No, you can't go in there.' Finally, they walked out, saw me and said, `Coach! How are you doing?' I said we wanted to have a gathering back at the house. Then, the governor said they were having a luncheon. The guys said, `No, we're going to Coach Mason's.'"

The question is where Mason will go with all his free time. He has ruled out broadcasting, saying he isn't good enough, but has left the door open for anything else that doesn't interfere with Labor Day gatherings at his place in Port Albert, Ontario, about 90 miles north of Port Huron.

"I'll be down for all the football games," Mason said. "And I'll go down to Florida when the weather gets bad. I've had calls from people about different things. Maybe I'll consult for former players. And if I could do something for the CCHA or college hockey, that would be good."

If that doesn't happen, friends and family will be amazed. Mason doesn't do bored very well, as his wife, Marion, and daughters, Tracey and Cindy, could tell you.

"For the first little while, he'll really enjoy it," Marion said. "He'll have no stress, no decisions to make and no meetings to attend. But by December, he'll be walking around like a lost puppy. He'll have to do something in hockey somewhere. I know his grandson, Travis, hasn't had a chance to learn much hockey from him. Ron did fill in as his coach for three games at a youth tournament in Houghton and lost all three."

Mason hasn't lost often and won't lose sleep over anything that has happened in a career with more impact than any Ryan Miller save.

He said he'll play a little more golf. And you know he will.

He said he'll catch the fish or two that has eluded his lures. There's no doubt he will.

Finally, he said he'll watch his grandson play hockey as often as he can now. Better save a seat - or room to pace.

With Mason, where there's a will, there's always a way. His way.